Asia’s Nuclear Cradle: What China Stands to Gain from Kashmir

Asia’s Nuclear Cradle: What China Stands to Gain from Kashmir

Asia’s Nuclear Cradle: What China Stands to Gain from Kashmir

Kashmir persists not by accident but design: China manages the dispute to protect its hegemony, yet demographic and resource pressures threaten this strategy’s future.

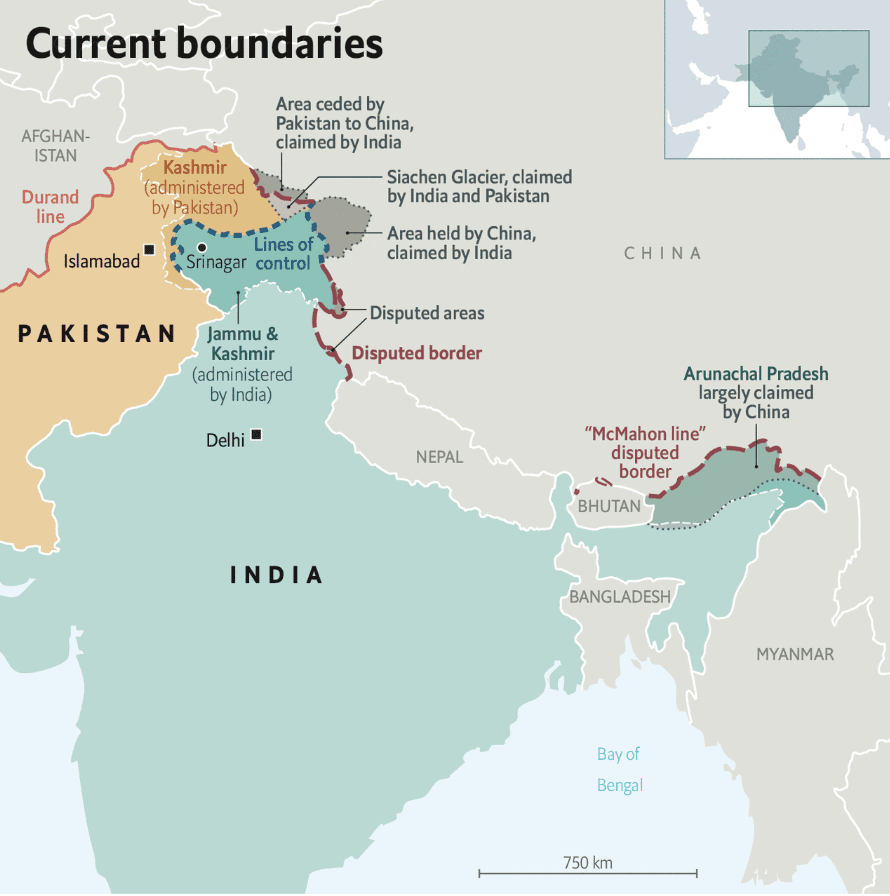

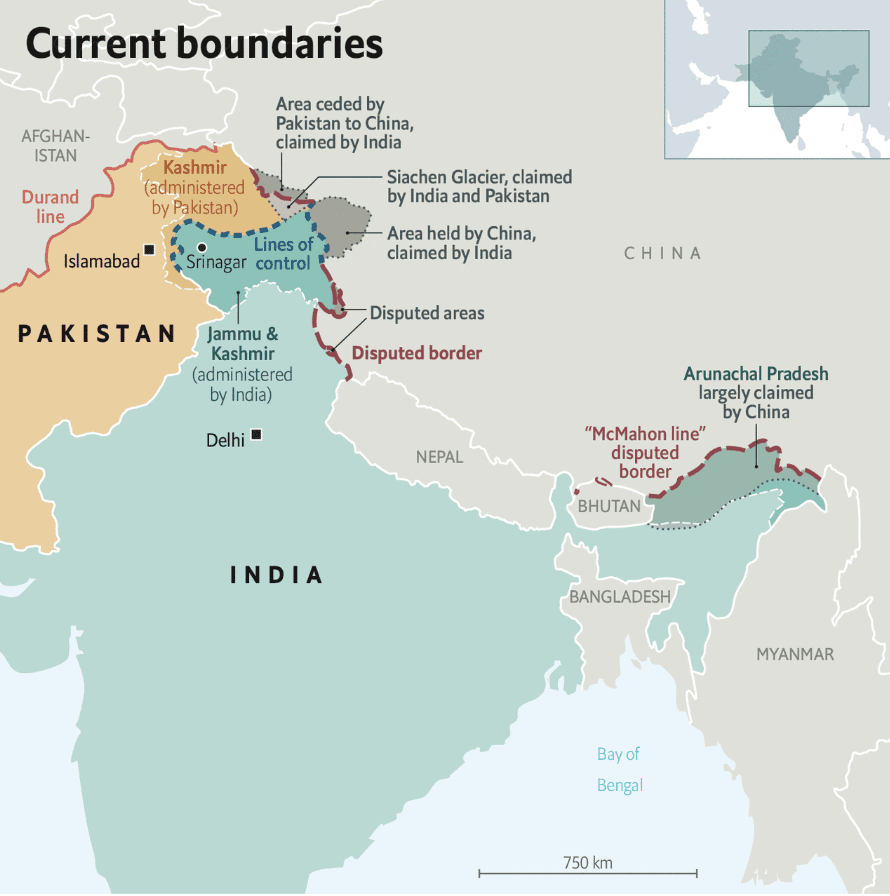

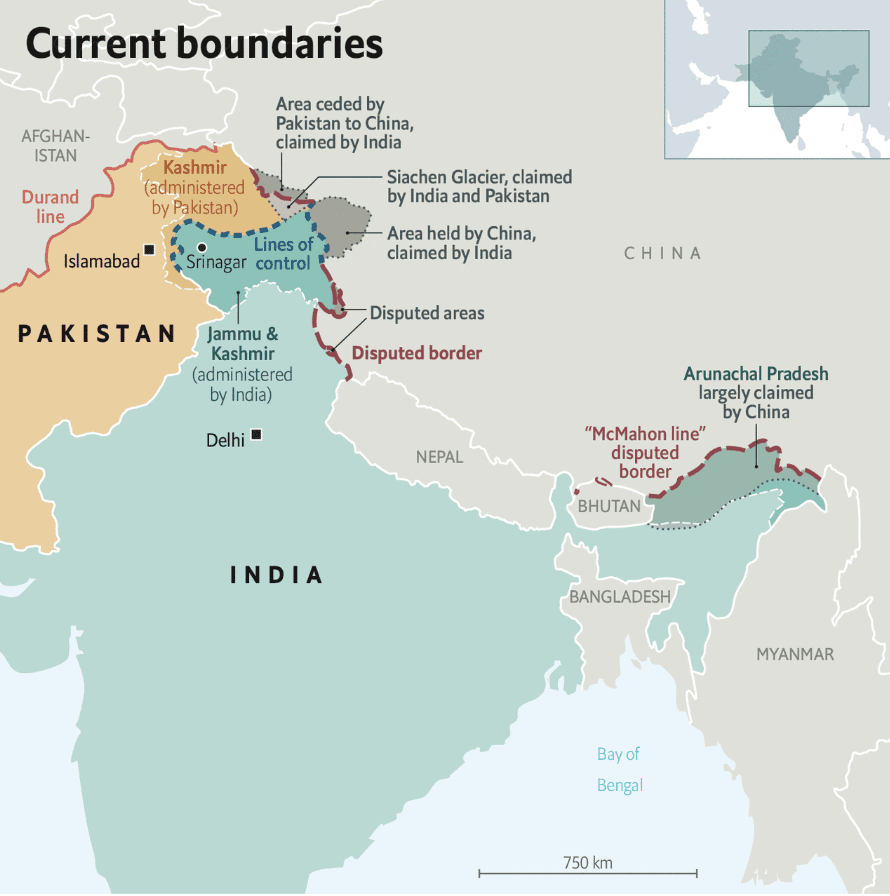

What is it that motivates those states—populous or affluent as they may be—to lay claim to such contested territory? Kashmir, tucked away in a valley and cradled by three nuclear powers, has become the focal point of an enduring conflict that surpasses a simple land struggle, reflecting deeper security anxieties in the region.

Of the more known Kashmiri centred conflicts are the sporadic Indo-Pakistani wars. Upon British India’s partition circa 1947, Maharaja Hari Singh, eventually acceded Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) to India, sparking the first Indo-Pakistani war. Though subsiding just over a year later, Pakistan persistently contested India’s sovereignty, advocating for democracy—through a UN-mandated plebiscite—due to Kashmirs majority Muslim demographic. Through this, Pakistan appealed to international actors by framing India as an impediment to the freedom and individual liberty of its approximate (pre-accession) 75% Muslim population, substantiating it’s claim of India’s “illegal occupation”. In response, India sought to consolidate legitimacy of its sovereignty through the revocation of article 370, dissolving Kashmir’s “special” autonomy. This allowed for India to further frame tensions with Kashmir as a domestic matter, subverting its status as “contested territory”. Proving to be a diplomatic deadlock, war has thus been India and Pakistan’s primary mode of catharsis, most recently resulting in the conflict of May 2025—the manifestation of a zero-sum fear.

Whilst India and Pakistan’s claim over Kashmir is inherent to their partition, China’s involvement indicates an opportunistic approach, catalysed by anxieties surrounding state security and regional influence. Commencing in 1954, China capitalised on ambiguous border demarcations, quietly building a national highway (G219) through contested Kashmir, subsequently escalating into the Sino-Indian war of 1962. Seizing Aksai Chin (roughly 15% of J&K) that same year, China was able to utilise the captured land to preserve its domestic security greatly. It used the G219 to connect Xinjiang and Tibet—two of China’s most sensitive regions—rendering Aksai Chin integral to China’s internal security. Yet, creating and defending this corridor alone was not sufficient for Beijing, as India’s unresolved claims for Kashmir continued to threaten China’s western frontier.

As such, it is China’s strategic alignment in the region post-1962 that provides insight on how it transformed internal security measures into a regional stabilising strategy. Approximately 4 months after the Sino-Indian war, China propositioned Pakistan regarding the bilateral demarcation of its Xinjiang region and Pakistan’s Gilgit-Baltistan (Kashmir). Through the 1963 Sino-Pakistan Boundary Agreement (SPBA), China succeeded in formalising its territorial acquisition the year prior; Pakistan had officially recognised Aksai Chin as China’s whilst also ceding the Trans Karakoram Tract (TKT). Islamabad’s willingness to cooperate in the aforementioned ways were to be expected; Pakistan’s hostility towards India prompted its alignment with any force opposing it—the enemy of its enemy.

For China, the strategic successes of the SPBA were many; first, in aligning with Pakistan—the underdog calling for Kashmir’s liberation—China postured itself as the protector of weaker neighbouring powers, legitimising its stakeholder status on the global stage. Moreover, China’s procurement of the TKT now stifled India’s diplomatic claim to more of Kashmir, ensuring that any future conflict couldn’t be justified by border ambiguity. It also secured China’s western frontier, creating a defensive depth that separated contested territory from its western-most supply routes and military corridors. Strategically, it enhanced China’s surveillance and fire-control over the Siachen Glacier—contested land to the south of the TKT that connects to India’s Ladakh through no defined boundary. All of these factors accumulated, thwarting India’s ability to regain its lost territory and undermining its regional presence. In effect, China established friendly relations with Pakistan without supplementing its strength, supporting Islamabad’s claim to Kashmir insofar as it served to balance regional powers.

It is exactly China’s aforementioned efforts that underscore contemporary south Asian security dynamics. For instance, during the Indo-Pakistani crisis of May 2025, Beijing’s ministry reiterated past sentiments, summarised aptly that “India and Pakistan are neighbours who cannot be moved away, and both are also China’s neighbours. China opposes all forms of terrorism”—a statement indicative of its stabilising role in the region. Yet, this restrained diplomatic posture also suggests that China had taken no formal sides, aiming instead to deescalate the Indo-Pakistani conflict without determining an actual resolution.

But, why then, does China seem reluctant to help in resolving the issue that is Kashmir? Well, beyond the looming risk of nuclear warfare, China holds concern that India gaining sovereignty over Kashmir entirely would threaten the existing Sino-Pakistan border. This is because article 6 of the SPBA stipulates it to be provisional, with boundary discussions set to reopen after the settlement of Kashmir. And although the SPBA may retain validity so long as the sovereign authority stays Pakistan—if seized by anyone else, the legal framework that entrenched China’s claim in the region would lose effect. India’s claim of the TKT could escalate tensions, necessitating a substantial increase in border militarisation and defence expenditure. As such, it would be counterproductive for China to be confronted with the finality of the Indo-Pak wars while it exerts military efforts against Taiwan. Were this to occur, China would be forced to divide its military prowess, spreading itself thin to secure its western and south-eastern frontiers. Ultimately, this means that China’s security stays most intact if Kashmir remains contested territory.

To speculate even further, Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) is expected to host its largest dam, the Diamer-Bhasha, come 2029. Able to hold approximately 8.1 million acre-feet of water, it will serve to reduce water stress across Pakistan through increased storage and improved irrigation—placing one of Pakistan’s lifelines in unsettled territory. Seeing as the Diamer-Bhasha dam is meant to aid water reserves and agriculture, if India were to gain sovereignty over GB it would control a portion of Pakistan’s vital hydro-infrastructure, assets New-Dheli could utilise to strategically weaken Pakistan. India’s leverage over Pakistan would create a power struggle in the region, a result that could force Beijing into a reactive role in the region, diminishing China’s capacity to exert influence—whether domestically or internationally. And although improbable that India would ever do so, if tensions between it and Pakistan were to ever escalate into full-scale war, the possibility could not be excluded.

If, however, the inverse was to occur, Pakistan’s sovereignty over India-administered Kashmir would also increase its regional influence exponentially. As a state whose foreign policy is explicitly formed by an Islamic political identity, Pakistan seizing Kashmir could introduce a new axis of competition into Beijing’s periphery through issues of religion and identity. Considering, for instance, Aksai Chin’s proximity to China’s Muslim-majority Xinjiang, Pakistan may find interest in prodding around the Line of Actual Control—the boundary separating Ladakh and Aksai Chin—advocating for the same freedom of self-determination of Muslims it once did with J&K and Ladakh. These political expectations would be reinforced by Pakistan’s evolving material capabilities, particularly in light of the recent Saudi-Pakistan defence pact (SPDP), a deal which saw a deeper defence coordination between Riyadh and Islamabad within the broader Middle East-South Asia (MESA) region.

Ultimately, for China, it seems that Kashmir’s repression endures not because of its inability to be resolved, but because its unresolved status is strategically useful to its hegemony. Thus, China’s conduct during the Indo-Pak crises has actively served to de-escalate without resolving, to manage without settling. Yet, the long-term sustainability of this strategy remains in question. Domestic insecurities, such as China’s declining population size and its rising water stress point toward a gradual erosion of the foundational components that China’s hegemony is built on—manpower and energy production. As these insecurities accumulate over the coming century, Beijing’s ability to indefinitely preserve regional power, and international influence may be continually constrained if not addressed correctly, exposing the limits of China’s current regional stabilisation.

What is it that motivates those states—populous or affluent as they may be—to lay claim to such contested territory? Kashmir, tucked away in a valley and cradled by three nuclear powers, has become the focal point of an enduring conflict that surpasses a simple land struggle, reflecting deeper security anxieties in the region.

Of the more known Kashmiri centred conflicts are the sporadic Indo-Pakistani wars. Upon British India’s partition circa 1947, Maharaja Hari Singh, eventually acceded Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) to India, sparking the first Indo-Pakistani war. Though subsiding just over a year later, Pakistan persistently contested India’s sovereignty, advocating for democracy—through a UN-mandated plebiscite—due to Kashmirs majority Muslim demographic. Through this, Pakistan appealed to international actors by framing India as an impediment to the freedom and individual liberty of its approximate (pre-accession) 75% Muslim population, substantiating it’s claim of India’s “illegal occupation”. In response, India sought to consolidate legitimacy of its sovereignty through the revocation of article 370, dissolving Kashmir’s “special” autonomy. This allowed for India to further frame tensions with Kashmir as a domestic matter, subverting its status as “contested territory”. Proving to be a diplomatic deadlock, war has thus been India and Pakistan’s primary mode of catharsis, most recently resulting in the conflict of May 2025—the manifestation of a zero-sum fear.

Whilst India and Pakistan’s claim over Kashmir is inherent to their partition, China’s involvement indicates an opportunistic approach, catalysed by anxieties surrounding state security and regional influence. Commencing in 1954, China capitalised on ambiguous border demarcations, quietly building a national highway (G219) through contested Kashmir, subsequently escalating into the Sino-Indian war of 1962. Seizing Aksai Chin (roughly 15% of J&K) that same year, China was able to utilise the captured land to preserve its domestic security greatly. It used the G219 to connect Xinjiang and Tibet—two of China’s most sensitive regions—rendering Aksai Chin integral to China’s internal security. Yet, creating and defending this corridor alone was not sufficient for Beijing, as India’s unresolved claims for Kashmir continued to threaten China’s western frontier.

As such, it is China’s strategic alignment in the region post-1962 that provides insight on how it transformed internal security measures into a regional stabilising strategy. Approximately 4 months after the Sino-Indian war, China propositioned Pakistan regarding the bilateral demarcation of its Xinjiang region and Pakistan’s Gilgit-Baltistan (Kashmir). Through the 1963 Sino-Pakistan Boundary Agreement (SPBA), China succeeded in formalising its territorial acquisition the year prior; Pakistan had officially recognised Aksai Chin as China’s whilst also ceding the Trans Karakoram Tract (TKT). Islamabad’s willingness to cooperate in the aforementioned ways were to be expected; Pakistan’s hostility towards India prompted its alignment with any force opposing it—the enemy of its enemy.

For China, the strategic successes of the SPBA were many; first, in aligning with Pakistan—the underdog calling for Kashmir’s liberation—China postured itself as the protector of weaker neighbouring powers, legitimising its stakeholder status on the global stage. Moreover, China’s procurement of the TKT now stifled India’s diplomatic claim to more of Kashmir, ensuring that any future conflict couldn’t be justified by border ambiguity. It also secured China’s western frontier, creating a defensive depth that separated contested territory from its western-most supply routes and military corridors. Strategically, it enhanced China’s surveillance and fire-control over the Siachen Glacier—contested land to the south of the TKT that connects to India’s Ladakh through no defined boundary. All of these factors accumulated, thwarting India’s ability to regain its lost territory and undermining its regional presence. In effect, China established friendly relations with Pakistan without supplementing its strength, supporting Islamabad’s claim to Kashmir insofar as it served to balance regional powers.

It is exactly China’s aforementioned efforts that underscore contemporary south Asian security dynamics. For instance, during the Indo-Pakistani crisis of May 2025, Beijing’s ministry reiterated past sentiments, summarised aptly that “India and Pakistan are neighbours who cannot be moved away, and both are also China’s neighbours. China opposes all forms of terrorism”—a statement indicative of its stabilising role in the region. Yet, this restrained diplomatic posture also suggests that China had taken no formal sides, aiming instead to deescalate the Indo-Pakistani conflict without determining an actual resolution.

But, why then, does China seem reluctant to help in resolving the issue that is Kashmir? Well, beyond the looming risk of nuclear warfare, China holds concern that India gaining sovereignty over Kashmir entirely would threaten the existing Sino-Pakistan border. This is because article 6 of the SPBA stipulates it to be provisional, with boundary discussions set to reopen after the settlement of Kashmir. And although the SPBA may retain validity so long as the sovereign authority stays Pakistan—if seized by anyone else, the legal framework that entrenched China’s claim in the region would lose effect. India’s claim of the TKT could escalate tensions, necessitating a substantial increase in border militarisation and defence expenditure. As such, it would be counterproductive for China to be confronted with the finality of the Indo-Pak wars while it exerts military efforts against Taiwan. Were this to occur, China would be forced to divide its military prowess, spreading itself thin to secure its western and south-eastern frontiers. Ultimately, this means that China’s security stays most intact if Kashmir remains contested territory.

To speculate even further, Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) is expected to host its largest dam, the Diamer-Bhasha, come 2029. Able to hold approximately 8.1 million acre-feet of water, it will serve to reduce water stress across Pakistan through increased storage and improved irrigation—placing one of Pakistan’s lifelines in unsettled territory. Seeing as the Diamer-Bhasha dam is meant to aid water reserves and agriculture, if India were to gain sovereignty over GB it would control a portion of Pakistan’s vital hydro-infrastructure, assets New-Dheli could utilise to strategically weaken Pakistan. India’s leverage over Pakistan would create a power struggle in the region, a result that could force Beijing into a reactive role in the region, diminishing China’s capacity to exert influence—whether domestically or internationally. And although improbable that India would ever do so, if tensions between it and Pakistan were to ever escalate into full-scale war, the possibility could not be excluded.

If, however, the inverse was to occur, Pakistan’s sovereignty over India-administered Kashmir would also increase its regional influence exponentially. As a state whose foreign policy is explicitly formed by an Islamic political identity, Pakistan seizing Kashmir could introduce a new axis of competition into Beijing’s periphery through issues of religion and identity. Considering, for instance, Aksai Chin’s proximity to China’s Muslim-majority Xinjiang, Pakistan may find interest in prodding around the Line of Actual Control—the boundary separating Ladakh and Aksai Chin—advocating for the same freedom of self-determination of Muslims it once did with J&K and Ladakh. These political expectations would be reinforced by Pakistan’s evolving material capabilities, particularly in light of the recent Saudi-Pakistan defence pact (SPDP), a deal which saw a deeper defence coordination between Riyadh and Islamabad within the broader Middle East-South Asia (MESA) region.

Ultimately, for China, it seems that Kashmir’s repression endures not because of its inability to be resolved, but because its unresolved status is strategically useful to its hegemony. Thus, China’s conduct during the Indo-Pak crises has actively served to de-escalate without resolving, to manage without settling. Yet, the long-term sustainability of this strategy remains in question. Domestic insecurities, such as China’s declining population size and its rising water stress point toward a gradual erosion of the foundational components that China’s hegemony is built on—manpower and energy production. As these insecurities accumulate over the coming century, Beijing’s ability to indefinitely preserve regional power, and international influence may be continually constrained if not addressed correctly, exposing the limits of China’s current regional stabilisation.

What is it that motivates those states—populous or affluent as they may be—to lay claim to such contested territory? Kashmir, tucked away in a valley and cradled by three nuclear powers, has become the focal point of an enduring conflict that surpasses a simple land struggle, reflecting deeper security anxieties in the region.

Of the more known Kashmiri centred conflicts are the sporadic Indo-Pakistani wars. Upon British India’s partition circa 1947, Maharaja Hari Singh, eventually acceded Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) to India, sparking the first Indo-Pakistani war. Though subsiding just over a year later, Pakistan persistently contested India’s sovereignty, advocating for democracy—through a UN-mandated plebiscite—due to Kashmirs majority Muslim demographic. Through this, Pakistan appealed to international actors by framing India as an impediment to the freedom and individual liberty of its approximate (pre-accession) 75% Muslim population, substantiating it’s claim of India’s “illegal occupation”. In response, India sought to consolidate legitimacy of its sovereignty through the revocation of article 370, dissolving Kashmir’s “special” autonomy. This allowed for India to further frame tensions with Kashmir as a domestic matter, subverting its status as “contested territory”. Proving to be a diplomatic deadlock, war has thus been India and Pakistan’s primary mode of catharsis, most recently resulting in the conflict of May 2025—the manifestation of a zero-sum fear.

Whilst India and Pakistan’s claim over Kashmir is inherent to their partition, China’s involvement indicates an opportunistic approach, catalysed by anxieties surrounding state security and regional influence. Commencing in 1954, China capitalised on ambiguous border demarcations, quietly building a national highway (G219) through contested Kashmir, subsequently escalating into the Sino-Indian war of 1962. Seizing Aksai Chin (roughly 15% of J&K) that same year, China was able to utilise the captured land to preserve its domestic security greatly. It used the G219 to connect Xinjiang and Tibet—two of China’s most sensitive regions—rendering Aksai Chin integral to China’s internal security. Yet, creating and defending this corridor alone was not sufficient for Beijing, as India’s unresolved claims for Kashmir continued to threaten China’s western frontier.

As such, it is China’s strategic alignment in the region post-1962 that provides insight on how it transformed internal security measures into a regional stabilising strategy. Approximately 4 months after the Sino-Indian war, China propositioned Pakistan regarding the bilateral demarcation of its Xinjiang region and Pakistan’s Gilgit-Baltistan (Kashmir). Through the 1963 Sino-Pakistan Boundary Agreement (SPBA), China succeeded in formalising its territorial acquisition the year prior; Pakistan had officially recognised Aksai Chin as China’s whilst also ceding the Trans Karakoram Tract (TKT). Islamabad’s willingness to cooperate in the aforementioned ways were to be expected; Pakistan’s hostility towards India prompted its alignment with any force opposing it—the enemy of its enemy.

For China, the strategic successes of the SPBA were many; first, in aligning with Pakistan—the underdog calling for Kashmir’s liberation—China postured itself as the protector of weaker neighbouring powers, legitimising its stakeholder status on the global stage. Moreover, China’s procurement of the TKT now stifled India’s diplomatic claim to more of Kashmir, ensuring that any future conflict couldn’t be justified by border ambiguity. It also secured China’s western frontier, creating a defensive depth that separated contested territory from its western-most supply routes and military corridors. Strategically, it enhanced China’s surveillance and fire-control over the Siachen Glacier—contested land to the south of the TKT that connects to India’s Ladakh through no defined boundary. All of these factors accumulated, thwarting India’s ability to regain its lost territory and undermining its regional presence. In effect, China established friendly relations with Pakistan without supplementing its strength, supporting Islamabad’s claim to Kashmir insofar as it served to balance regional powers.

It is exactly China’s aforementioned efforts that underscore contemporary south Asian security dynamics. For instance, during the Indo-Pakistani crisis of May 2025, Beijing’s ministry reiterated past sentiments, summarised aptly that “India and Pakistan are neighbours who cannot be moved away, and both are also China’s neighbours. China opposes all forms of terrorism”—a statement indicative of its stabilising role in the region. Yet, this restrained diplomatic posture also suggests that China had taken no formal sides, aiming instead to deescalate the Indo-Pakistani conflict without determining an actual resolution.

But, why then, does China seem reluctant to help in resolving the issue that is Kashmir? Well, beyond the looming risk of nuclear warfare, China holds concern that India gaining sovereignty over Kashmir entirely would threaten the existing Sino-Pakistan border. This is because article 6 of the SPBA stipulates it to be provisional, with boundary discussions set to reopen after the settlement of Kashmir. And although the SPBA may retain validity so long as the sovereign authority stays Pakistan—if seized by anyone else, the legal framework that entrenched China’s claim in the region would lose effect. India’s claim of the TKT could escalate tensions, necessitating a substantial increase in border militarisation and defence expenditure. As such, it would be counterproductive for China to be confronted with the finality of the Indo-Pak wars while it exerts military efforts against Taiwan. Were this to occur, China would be forced to divide its military prowess, spreading itself thin to secure its western and south-eastern frontiers. Ultimately, this means that China’s security stays most intact if Kashmir remains contested territory.

To speculate even further, Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) is expected to host its largest dam, the Diamer-Bhasha, come 2029. Able to hold approximately 8.1 million acre-feet of water, it will serve to reduce water stress across Pakistan through increased storage and improved irrigation—placing one of Pakistan’s lifelines in unsettled territory. Seeing as the Diamer-Bhasha dam is meant to aid water reserves and agriculture, if India were to gain sovereignty over GB it would control a portion of Pakistan’s vital hydro-infrastructure, assets New-Dheli could utilise to strategically weaken Pakistan. India’s leverage over Pakistan would create a power struggle in the region, a result that could force Beijing into a reactive role in the region, diminishing China’s capacity to exert influence—whether domestically or internationally. And although improbable that India would ever do so, if tensions between it and Pakistan were to ever escalate into full-scale war, the possibility could not be excluded.

If, however, the inverse was to occur, Pakistan’s sovereignty over India-administered Kashmir would also increase its regional influence exponentially. As a state whose foreign policy is explicitly formed by an Islamic political identity, Pakistan seizing Kashmir could introduce a new axis of competition into Beijing’s periphery through issues of religion and identity. Considering, for instance, Aksai Chin’s proximity to China’s Muslim-majority Xinjiang, Pakistan may find interest in prodding around the Line of Actual Control—the boundary separating Ladakh and Aksai Chin—advocating for the same freedom of self-determination of Muslims it once did with J&K and Ladakh. These political expectations would be reinforced by Pakistan’s evolving material capabilities, particularly in light of the recent Saudi-Pakistan defence pact (SPDP), a deal which saw a deeper defence coordination between Riyadh and Islamabad within the broader Middle East-South Asia (MESA) region.

Ultimately, for China, it seems that Kashmir’s repression endures not because of its inability to be resolved, but because its unresolved status is strategically useful to its hegemony. Thus, China’s conduct during the Indo-Pak crises has actively served to de-escalate without resolving, to manage without settling. Yet, the long-term sustainability of this strategy remains in question. Domestic insecurities, such as China’s declining population size and its rising water stress point toward a gradual erosion of the foundational components that China’s hegemony is built on—manpower and energy production. As these insecurities accumulate over the coming century, Beijing’s ability to indefinitely preserve regional power, and international influence may be continually constrained if not addressed correctly, exposing the limits of China’s current regional stabilisation.